August 13, 2023

Some of you know I’ve got a novel in the works. What follows is my story of birthing this book. It has required focus, faith, determination: in a word, persistence, the quality that all worthwhile creative work asks of us.

Along the way, I’ve developed tools and sought out resources to help me maintain my love of writing. I’m not a full-time writer, but I teach writing. I thought this recounting of my journey might be instructive to my students and of interest to my readers. You.

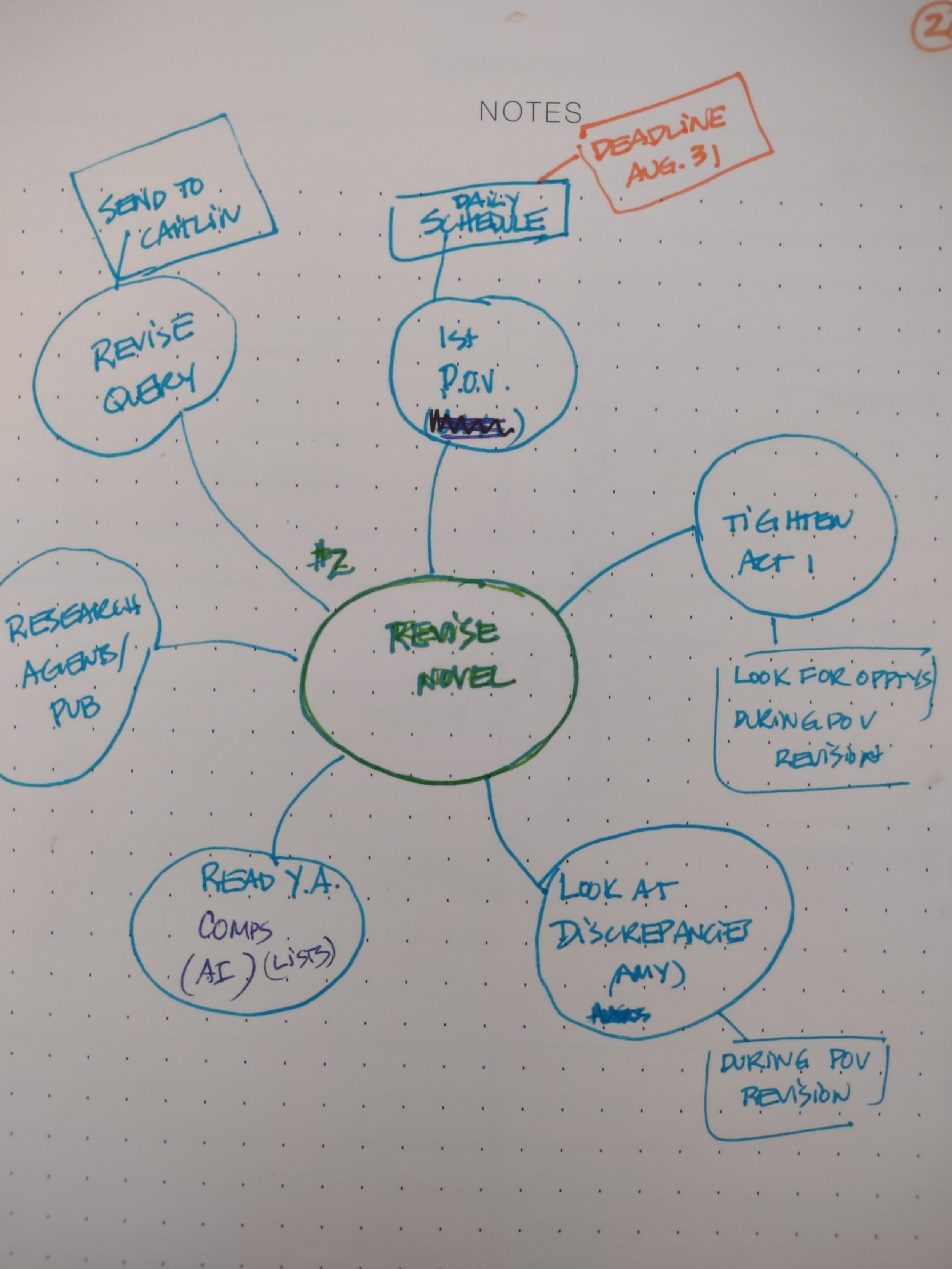

One of my favorite planning tools is a mind map, seen above. It’s an intuitive way to map out a project sans the pressure of linear planning. You can see I’ve got tasks and sub-tasks identified, and I can easily add additional ones. This mind map represents my most recent novel revision, the one I never expected to be undertaking.

But let’s start at the beginning.

Novel, Take 1

I never intended to write a novel. I had completed my masters thesis on women composers, at 100 pages the longest piece of writing I’d ever undertaken. I found I loved the whole process of research, drafting, and revising. Although I’d kept journals for years and taken a few stabs at poems and short prose, I’d never taken my creative writing seriously. Now I was eager to dive in.

I began, as many beginning writers do, with personal essays. I found a writing teacher and a group and continued writing from my life. Until I received an idea for a story. The premise: a teen-age girl is involved in a car accident which kills her father. The story called to me. I couldn’t stop thinking about how the girl, whom I called Katie, managed to live with what had happened.

I wrote the first chapter in an unknowing state. The material felt channeled through me. I continued that way in a semi-trance state. I can remember walking out of my studio after a writing session in a daze. It was my first encounter with the muse. Since then, I’ve found this is the way stories come to me and think of myself as the vehicle or vessel for a story that has chosen me as its scribe.

After sharing chunks of the novel with my weekly writing group, I was happy with my accomplishment and naively sent it off to a few agents. I anticipated an enthusiastic response which included not only an offer of representation, but a decent (maybe six-figure?) advance. Bliss is the product of ignorance. The book wasn’t anywhere near ready, nor was I.

I put the novel aside when the March Farm book called my name. The entire process of creating that book, submitting it to agents and publishers, and in the end, publishing and printing it myself, took eight years.

A perennial student, I then pursued another graduate degree, this time in writing.

Novel, Take 2

In 2017, after finishing grad school, I returned to the novel with a new concept for the book: six months after the accident, Katie attends a grief camp for girls who have been traumatized by the death of a loved one. Katie’s mother has not been able to forgive her, so she is dealing with loss complicated by guilt. At grief camp, she finds the support and fellow travelers she needs to face her grief squarely.

In 2017, I was accepted into a week-long creative residency at a Drop Forge & Toolin Hudson, New York. There I fleshed out the grief camp chapters, which take up about two-thirds of the story. I then took the full draft through two writing groups. My next step was gathering input from three beta readers who would read it and give me honest feedback. A beta reader is a person who, unlike your writing group partners, is not invested in your project, is an avid reader, and is willing to provide objective feedback. They are the closest you’ll get to the stranger who picks up your creation in a bookstore or library and hopefully takes it home with them.

After making the revisions suggested by the beta readers, it was mid-2020. The book was ready for a developmental edit, which includes editorial suggestions on structure, pacing, and characterization, as well as detailed line edits throughout the manuscript.

That revision took about six months. I sent it off to my copy editor, who corrected grammar, checked facts, and made the whole book read smoother. A shorter round of revision ensued, then I was ready to submit the book to literary agents, the gatekeepers for a traditional publishing deal with one of the Big Four publishers.

By now, it’s 2021. I identified appropriate literary agents, wrote a query letter (a half-page letter to snag an agent’s attention), a synopsis (a single-spaced one-page summary of the book), and looked for “comps,” comparative titles in the current marketplace. These help the agent slot the book correctly and determine to which publishers she’ll pitch it.

I won’t go into the details of researching and submitting to an agent, but I can assure you it’s a dreaded, time-consuming, and soul-crushing task. There are so many writers seeking publication today that agents don’t respond to queries they’re not interested in, not even with a form email that says, “Sorry, not for me,” but in a slightly nicer way. Writers are left sitting in a void wondering if any human pair of eyes read their carefully crafted query. The whole process is not for sissies.

Novel, Take 3

I spent over a year submitting to agents and extended my search to independent publishers. Each submission requires a different set of materials: a query letter only; a query and a synopsis; a query, synopsis, and the first 10 or 20 or 50 pages; all of the above plus comps published within the last three years. (My very best comp, Ordinary People by Judith Guest was published in 1976 and made into a movie in 1980.) What every writer hopes for is a request for a “full,” that is, the full manuscript.

No nibbles. I followed Courtney Maum’s (novelist, memoirist, savvy publishing expert) advice: if you’ve submitted to 10 to 20 agents and no one has asked for a “full,” you need to take another look at either the book or the query—or both. I felt confident in my query. It had been reviewed by another editor, so it was time to seek another editorial opinion on the book itself. By now, I knew what questions to ask: I wanted a high level overview of my book, identification of any holes in the story, and advice as to which genre the book belonged to.

The genre question was a big concern. It determined where I’d submit it, since agents and publishers focus on certain genres. Since the book features a seventeen-year-old protagonist, it falls into the YA (Young Adult) category. However, it doesn’t read like YA that is published today and, since it’s a mother-daughter story, I thought it might fall into Women’s Fiction. It’s more “literary,” which means it’s more character-based, and isn’t a “grab you by the lapels and don’t let go” kind of story. Of course, I want my readers to hook my readers and have them eager to turn the pages, but I also want them to sink into the experience of reading. That’s the kind of book I like to read, and it’s the kind I write. Plus, it’s written in third-person point-of-view, and most YA today is written in first-person. My general preference for novels is third-person, using the “she or he” pronoun, as I find it more flexible than first-person, which uses the “I” pronoun.

But deciding genre helps agents, publishers, and booksellers know where to slot the book, i.e., what shelf it belongs on and which audience to target. So it was important to determine it before I tackled another round of submissions.

In a few weeks, Amy, my big-picture editor, delivered the answers:

Make it YA, unless I wanted to expand Katie’s mother’s (Maureen) story.

Change the title - mine was too confusing.

Revise it to first-person POV.

Tighten Act 1 and fix a few small plot holes.

But, “I’m close.’